The Man from Mississippi

June 15, 2019

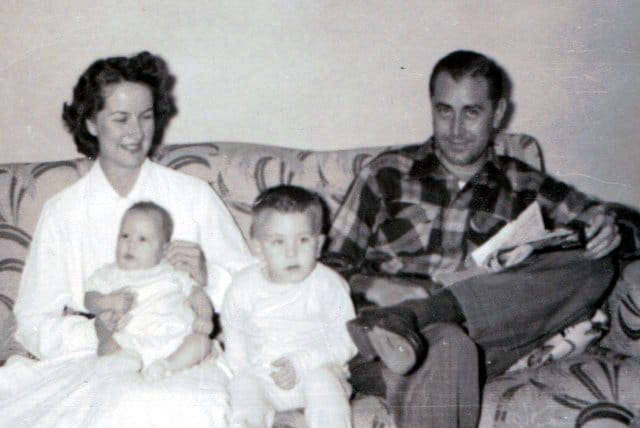

I don’t have many pictures of me with my dad.

I suppose this isn’t unusual given that he died long before digital cameras and smartphones made picture taking easy. I have vague memories of my dad taking home movies with an ancient 8mm camera. No sound, of course. Just pictures of us boys cavorting in the yard. There are a few pictures of him posing with his four sons. I know that because I’ve seen them over the years. At the moment I have no idea where those pictures are.

So this one will have to do.

The note on the back says it was taken in 1953 when I was a year old. That’s me sitting on my mother’s lap with my brother Andy (who would have been 3) sitting between Mom and Dad. And that’s my father on the right. I don’t really remember him that way. He looks too young in that picture. I think he was about 37 years old. Most of the other pictures of him that I do remember come from the 60s, when he was in his late 40s and early 50s.

Dad was a surgeon in a small town in Alabama. To say he was beloved would be putting it mildly. I was aware of that as I grew up, mostly because everywhere I went, I was always introduced as “Dr. Pritchard’s son.”

In 2004 as I was preaching through the Apostles Creed, I came to the phrase that calls God “the Father Almighty.” All week long I struggled with how to explain what those two words mean. Then it hit me. My dad was like a “father almighty” to me. I ended up writing a sermon called Who’s in Charge Here? What follows is what I wrote fifteen years ago, slightly updated. I offer it as my tribute to my dad on Father’s Day weekend.

Cow Poker

His story starts on a farm a few miles outside of Oxford, Mississippi. As a boy growing up on the farm, he learned how to hunt and fish, and he knew all about planting cotton and taking care of the horses and the cattle. He was a teenager during the Depression years when things were tough in Mississippi. He learned the value of hard work and the importance of saving every penny. After high school, he went off to college and then to the first two years of medical school. World War II intervened, and he became an Army doctor serving in Nome, Alaska. That’s where he met my mother, an Army nurse. After the war, they got married, and he graduated from Northwestern University Medical School in Chicago, which is where my older brother Andy was born. They moved to Memphis, Tennessee, where my brother Alan and I were born. Later he moved to Russellville, Alabama to take up the medical practice started by his brother Clarence, who died in 1954 of a brain hemorrhage. My brother Ron was born two years later.

My full name is Clarence Raymond Pritchard, taking my first name from my uncle and my middle name from my father’s middle name. That’s how I grew up in a small town in Alabama. And that’s where my dad lived until he died in 1974. We buried him on a hillside not far from his brother.

My dad came from another generation and followed another set of values. He always wore a coat and tie, he treated people with respect, he believed in good manners, and he didn’t think children should talk back to their parents. On that point, my father might be called old-fashioned. We never had debates about corporal punishment in our house. There was nothing to debate. Talk back or disobey and the punishment would be swift. I can still remember a few times when Mom would become so exasperated she would call him home from the clinic in the afternoon. That’s when we (my brothers and I) knew we had gone too far. “Please don’t call Dad,” we would say. But our pleas went unheeded. If he had to come home to discipline us, he would make sure it wasn’t a wasted trip.

But there is more to the story. Dad built a basketball goal in our back yard and occasionally shot baskets with us. He took us with him when he made house calls to homes in rural Franklin County. He would sing “The Donut Song” and a song about a cow on the railroad tracks. To keep us occupied on long trips, he taught us how to play “Cow Poker,” which isn’t as exotic as it sounds. We learned to love the Ole Miss Rebels because he took us to watch them play football 55 years ago. He was big on education. There was never any question that we were going to go to college. During my high school years he often came home late from the hospital. If he found us doing our homework, he would give us a quarter. I think I made 75 cents that way.

An “Old School” Father

He was “old school” in another way. Fathers today often try to be buddies and pals to their children. They want to be best friends with them. My dad would have been mystified by that approach. Parents are parents, kids are kids, and the world works best when we all remember where we belong. Dad didn’t come to my parties, and I didn’t go to his. He knew my friends, and they all said, “Hello, Dr. Pritchard,” when they saw him. Sometimes he would stop and chat for a moment—but only for a moment. Dad was not my best friend—he was my father. There is a huge difference.

We had a difficult relationship during my teenage years. He didn’t understand me very well, and I didn’t appreciate him as I should have. We had words on more than one occasion, and I said some things that weren’t very smart. Dad let me know what he thought in no uncertain terms. The strain lasted into my college years when I began feeling called to the ministry. I was young, immature, brash, and I didn’t know nearly as much as I thought I did. When I spoke of being a preacher, my dad made funny remarks, little quips that didn’t seem funny to me. But looking back, I see that he knew me better than I knew myself. With the wisdom that only a father can have, he saw that my life was shallow, that I lacked the character necessary to be a pastor. He never said it that way, but that’s what he meant. He knew that unless my life changed, I would not succeed.

In 1972 I attended a seminar where I heard for the very first time about the importance of a clear conscience. The speaker said we couldn’t be free to move forward until we asked forgiveness of those we had hurt. When he said that, I knew I had to go talk to my dad. That wasn’t an easy thing to do because he was my father and I was his son and talking like that didn’t come easy. But one night—I can see it in my mind’s eye—he was in his study at home, and I came in to see him. He was sitting at his desk catching up on some paperwork for the hospital, but he stopped what he was doing when I walked into the room. I stammered out something to the effect that I knew I had made a lot of mistakes and I knew I had hurt him and Mom by some of the things I had done and I wanted him to know I was sorry for everything. He looked at me for a moment, and then he said, “That’s all right, son.” That was it. If he said anything else, I don’t recall it, but I don’t think he did. Men of his generation seldom talked about their feelings. He didn’t say anything else, but he didn’t have to. When my father said, “That’s all right, son,” I knew I was forgiven.

From One Generation to Another

The next year Marlene and I got engaged, we graduated from college, and in June told my parents in Alabama that we wanted to get married in Phoenix, Arizona in August—six weeks later. Mom gasped, but Dad smiled. He was the best man at my wedding. I’m glad he met Marlene because he knew then I was bound to turn out okay.

Dad died a little over two months after we were married. It’s still hard for me to believe. He was so healthy, then he was sick for two weeks, and then he was gone. One moment remains in my mind. After the funeral, Marlene and I were driving from Alabama back to Dallas where I was a first-year seminary student. Somewhere just across the Mississippi border I began to cry. I was driving and crying, and I told Marlene a secret I had never shared with anyone. For a long time I had dreamed of having a son and naming him after my father. I wept because he did not live to see it happen. Five years later our first son was born. We named him Joshua Tyrus, after my father, Tyrus Pritchard.

Several years later Mark came along. Then Nick was born. Fast forward almost 40 years. Now we have three beautiful daughters-in-law—Leah, Vanessa, and Sarah, and eight splendid grandchildren—Knox, Eli, Penny, Violet, Zoe, Hannah, Josh, and Nico. I am sorry my father never knew his grandchildren, and they never knew him. But I am gladdened by the thought (which is a certainty in my mind) that my father would be proud and happy about my family. I have already lived longer than he did, and I know some part of him lives on in me and in my brothers. And so the family heritage is passed on from one generation to another.

After he died, it took me a while to see my father properly. Always he had been there whenever I needed him. He could answer any question and solve any problem. I still miss him 45 years later. He was a “father almighty” to me, and I’m happy to pay tribute to him on this Father’s Day weekend.